Investing in the joy of reading

Written by Sarah Crown, Director of Literature

But as the national development agency for literature, it’s vital that we respond to changes in the sector, and beyond. To do this, we listen closely to what professionals, the public, and our own research and data are telling us. All of this helps make sure that our attention and investment are focused on the areas where they are most needed, and where they will make the most difference. And it’s due to this approach that, over the last five years, we have been concentrating time and funding on one of the biggest challenges currently facing the literature sector: falling rates of reading.

Literature funding

It wasn’t always like this. While there’s case to be made that every Literature investment we make supports reading indirectly, a direct focus on reading for pleasure is something that Arts Council England has come to relatively recently. We took on responsibility for the funding and development of Literature in 1965 – 20 years after the Arts Council was founded.

At that time, and for decades afterwards, the focus of our investment and development work fell firmly onto writers and writing. In particular, we concentrated on strengthening forms of writing that the market wasn’t already supporting, such as poetry, literature in translation, and literary fiction. Commercial publishing was in excellent health, and all the way into the 2000s, reading – as a leisure activity; as a way to relax – was so universal that it was almost invisible.

While we invested in literacy in the context of children and young people, with the aim of supporting them on their journey into a reading adulthood, the assumption was that once people knew how to read, the job was done.

Reading was embedded in our education system; it was woven through our daily lives; as the only portable form of entertainment, it had a lock on our attention. We were all doing it, all of the time. And in the absence of other options, there was no real need to think about audience development – an activity that is so important to other artforms.

Delegates from UNESCO Cities of Literature across the world visit Norfolk & Norwich Millennium Library as part of Nottwich © Hannah Hutchins

Delegates from UNESCO Cities of Literature across the world visit Norfolk & Norwich Millennium Library as part of Nottwich © Hannah Hutchins

What else, after all, was there to do on the bus into work, short of staring out of the window?

The impact of new media

It can be hard to recognise change as it is happening. It’s often only with hindsight that things become clear. In 2007, after a decade of upheaval in the commercial literature sector which saw the death of the Net Book Agreement, the birth of Amazon, and the launch of the Kindle, two things happened. At the time, they appeared to have little to do with readers. But from the vantage point of 2024, we can see that they changed our relationship with books far more significantly than anything that had happened in the decade before. Firstly, we went through the Global Financial Crisis, which caused spending on leisure to drop sharply. And in June of the same year, Apple launched its first iPhone – and called time on traditional books’ dominance of the portable entertainment arena. That looked back to the start of the 21st century.

It took time for the true impact of these events to be felt, and still more time for it to be understood. For a decade or so after 2007, the Literature sector continued to function as it always had, and the Arts Council did the same. But beneath the surface, things were changing. We began to hear more and more reports of growing uncertainty for authors, and all but the biggest publishers. In 2016, in order to test how serious these concerns were, we commissioned a research report into fiction sales t

In 2017, we published the findings of our research in a report known as the Canelo Report. The evidence it contained was clear: the supply chain from writer to reader was under intense pressure. Fiction sales had indeed fallen across the board since 2007, leaving publishers and writers exposed to significant financial risk. And crucially, where the rest of the economy had recovered after the Financial Crisis, fiction sales had failed to bounce back.

People had stopped buying books when times were tough, but they hadn’t started again once the crisis was over. Habits had changed. Books weren’t the only option anymore: now, they were competing with the likes of streaming services, gaming, social media – even work emails. The advent of mobile devices eroded books’ USP as the only portable form of entertainment. And the financial crisis hastened and embedded a decisive change in our collective behaviour. In many cases, the battle for people’s attention had been won by mobile devices.

Books matter

But does this matter? If people want to get their story fix from new media, rather than the printed page, is that really a problem we should be looking to solve? It’s important to ask the question, certainly – but the latest research strongly suggests that it matters very much. The way that we absorb stories, it turns out, is as important in its way as the stories themselves. A growing set of evidence links reading for pleasure – particularly of books that are rich in metaphor – with a range of health and wellbeing benefits.

These include increased empathy and socio-cultural development, enhanced concentration and analytical ability, improved mental health and memory, and reduced loneliness. Reading enriches and sustains us; it comforts and uplifts us. It offers effective and affordable support for a range of social, political and health challenges. It changes our hearts, our minds, and even our brains, in ways that we’re only just coming to understand. And these things don’t just benefit us as individuals, but as thinking, feeling societies too. Yet just as the breadth and depth of the benefits of reading are starting to be recognised, the impact of 2007 is presenting a very real threat to a pastime that had been taken for granted for nearly two centuries.

None of which, of course, is to reduce the artistic value of other media: the intensity and complexity of gaming; the visual richness and dramatic impact of great TV. But we mustn’t throw the baby out with the bathwater. If we don’t take steps to focus attention on the joys and advantages of reading, we could very quickly find ourselves in a world where it’s reduced to a limited pursuit. The social and cultural impact of such a shift should alarm us all.

The Reading agency image - Clovis Lowe

The Reading agency image - Clovis Lowe

© The Reader

© The Reader

Changing the narrative

That’s why we’ve spent the past half-decade refocusing our attention on the support and development of reading for pleasure. We believe that the joys and benefits of reading should be available to everyone, everywhere. To support this, we’ve developed stronger relationships with the commercial publishing sector, whose business is the business of reading. Their perspective and understanding of the literature sector, as well as their ability to coinvest with us on major projects, has significantly amplified those projects’ impact.

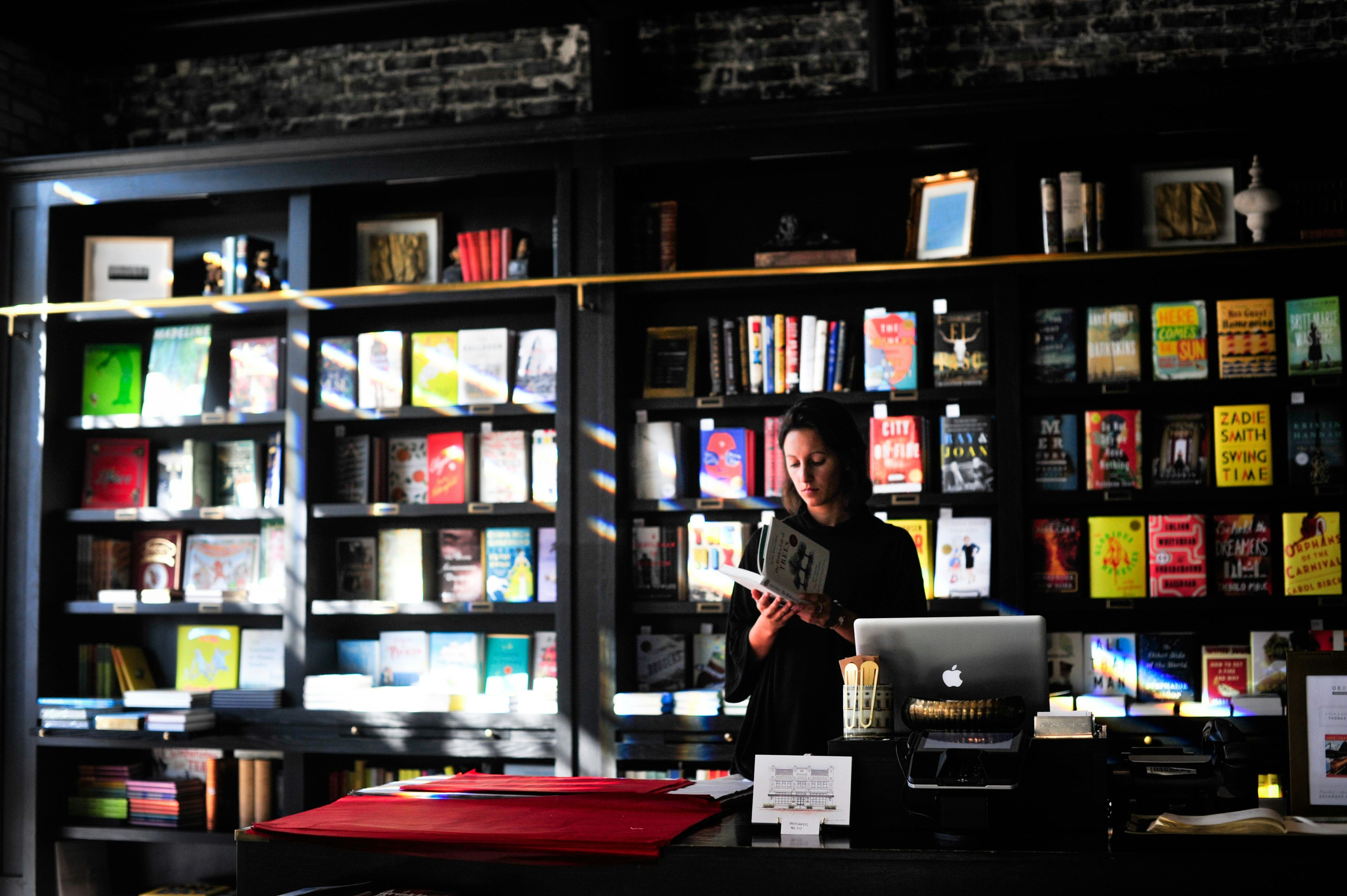

We’ve reached out to booksellers and bookshops – the engine-rooms of reader development – and started to forge partnerships that we believe will yield real benefits, for readers and for writers, in the years to come. We continue to champion the invaluable work of libraries, in every corner of the country. And we look for a focus on readers, on the audience as well as on the creators, in every Literature application we receive.

We’re also helping to shift the narrative of reading for pleasure through our funding for literature. In April 2023, Book Trust – the UK’s largest reading charity – joined the 2023-26 National Portfolio (NPO) – representing a significant increase in our national support for literature. Since 2019, our work with commercial partners has seen us invest in Connecting Stories, the National Literacy Trust’s countrywide network of Reading Hubs.

Over the same period, we’ve worked with major partners such as the BBC and The Reading Agency (also an NPO) to invest in projects including the Big Jubilee Read. And most recently, we’ve joined forces with Penguin Random House, the National Literary Trust, and our own libraries colleagues to make the case for the creation and growth of libraries in primary schools.

Alongside these investments that support the foundations of literacy across the country, we’ve supported a wide range of local initiatives. These range from the Shared Reading groups run by The Reader in Liverpool to reading schemes in prisons.

Throughout all our work in recent years – whether it is development, advocacy, or investment – support for the act of reading for pleasure has been central to our effort.

The full story

It’s important to say clearly that a step forward into the reading-for-pleasure arena doesn’t mean we’re taking a step back anywhere else. We’ll continue, as we have always done, to invest in the whole of the literature sector. This includes direct support to authors; and to independent publishers, who do such a fantastic job of seeking out and bringing to market the very best literary talent in our country. And to all the other organisations who together make up our brilliant, internationally renowned sector. In fact, we firmly believe that supporting and developing reading for pleasure is the most effective means there is of supporting the entire ecology of literature, from writers to publishers to bookshops.

Put simply, without readers, there is no literature ecology.

And in a world in which books are, for the first time in living memory, having to make the case for their place in the attention economy, the best and most sustainable way for the Arts Council to ensure the ongoing health of the entire literature sector is to help make that case too: to focus on developing readers, now and in the future.